An FDA for High-Risk Apps

Seeking evidence and nuance between calls for exemption and prohibition

It’s common sense that we need to repair our relationship with digital technologies to make them less addictive and isolating. At the same time, we’re rightfully wary of government regulation. We don’t want the government to dictate how we use our phones.

This tension between desiring freedom while recognizing harm has led to a debate at the extremes. One camp says, “Leave it to personal responsibility.” Another says, “Ban it all.”

Both extremes have surfaced this past month. President Trump’s December 11 executive order argues AI firms must be “free to innovate without cumbersome regulation,” while Senator Josh Hawley’s proposed GUARD Act would ban AI companions for minors.

But most of us are in the middle, sensing that neither shrugging it off nor banning it all is the right solution.

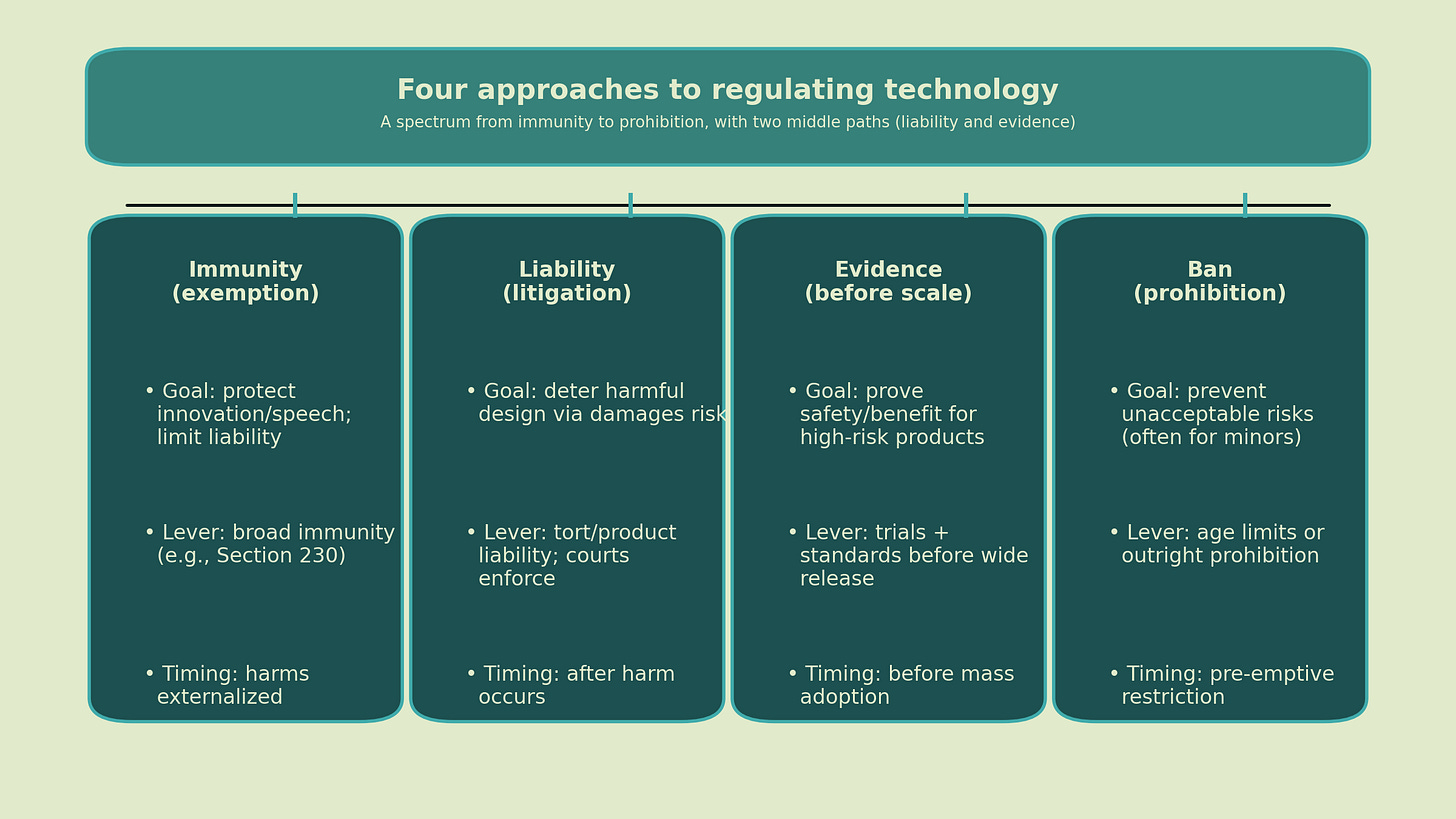

So here is a practical framework of four approaches to regulating high-risk online technologies that may provide some benefit and entertainment in moderation, but at the risk of compulsive use and harm. (For instance, online gambling, pornography, AI companions, and short-form video.) As you’ll see, I have a favorite approach among the four to generate evidence and incentivize design for wellbeing. Throughout this essay, I’ll mostly use AI companions to illustrate what an FDA-like precautionary approach could look like.

Stepping back from AI companions, though, there is a time and place for each approach.

After thirty-five years of the World Wide Web, there is a growing global consensus that we’re coming to “a definitive end to the internet’s laissez-faire era,” as Alan Z. Rozenshtein wrote in The Atlantic.

The central question is not whether we regulate, but how, when, and with what kind of evidence.

Immunity and exemption from liability

Section 230 is the cornerstone of legal immunity to technology companies. Without it, the early internet might have drowned in litigation instead of fueling a $2.6 trillion digital economy that now represents roughly 10 percent of US GDP. But thirty years later, the world’s most powerful companies have few incentives to design for our well-being.

Proponents of exemption argue we ought to tolerate some harm in exchange for more innovation and speech. That may be a reasonable bargain for a limited period of time, and there is danger in the pendulum swinging into the over-regulation of speech and amplification.

But without longer-term safeguards, we’ve normalized the development of products intentionally optimized for compulsion, outrage, and emotional dependency. AI is now set to super-charge that optimization.

Prohibition and bans

At the other extreme is prohibition. These advocates argue that some products or services are too risky to allow at all. Australia has banned social media for under-16s, with Denmark, Norway, Malaysia, and New Zealand looking to follow their lead.

China and Vietnam have caps and curfews on video games. South Korea did, too, until it proved too easy to circumvent and was overturned in 2021.

Cambodia, Albania, and India all banned online gambling after having legalized it.

Bans convey moral seriousness during a period of perceived spiritual crisis and social instability. And they can be justified when the expected harm is high, the user is vulnerable, and the product’s benefits are minimal. For instance, more than 80% of Brits support banning nudification apps and 84% of Americans would ban non-consensual deepfake porn.

But bans also have a long history of leading to evasion, uneven enforcement, substitution to the black market, and the rise of organized crime. For instance, criminalizing sex work increased sexually transmitted diseases in Indonesia and was associated with higher rates of sexual crimes in Europe. Similarly, restricting access to porn sites in the UK may drive users to more extreme content.

In retrospect, blanket bans are often rushed through in the midst of a moral panic. Even when justified, prohibition is a blunt instrument and should be treated as such.

Liability and litigation

Between the extremes of immunity and prohibition lie two middle paths. The first is a legalistic approach that sues for damages when products cause harm. “Litigation is the lowest-cost regulator for AI, forcing companies to internalize the costs of their product,” writes Civil rights attorney Joel Wertheimer.

Character.ai, for instance, has faced lawsuits alleging severe harms involving minors, including wrongful death. Legal advocates hope that liability is a strong incentive for responsible design. Companies that profit from risky platforms should face consequences when those risks materialize.

There’s an appeal to this approach. It doesn’t require the state to predict every harm in advance. It preserves innovation. And it uses the justice system to sort out negligence, intent, and damages. Using the analogy of tobacco, Bryce Bennett argues that product-liability lawsuits in the 1980s–90s ultimately forced tobacco companies to internalize the costs of harm, and prompted changes like warning labels and advertising restrictions.

But litigation is reactive. It arms lawyers to address harms after they happen. It’s expensive, slow, and a wildly inefficient way to generate evidence.

Cases can take years and are often settled without public clarity about what actually occurred. Even when plaintiffs win, we typically learn little about the design choices that caused harm or how to prevent them systematically.

The scientific path: evidence before scale

The second middle path is scientific, requiring rigorous evidence of safety and benefit before mass adoption.

The FDA already has a clinical testing process for “Software as a Medical Device” that has authorized products like:

NightWare, an Apple Watch app that detects nightmares

MamaLift, a smartphone app for postpartum depression

RelieVRx, a VR app to reduce chronic lower back pain

If you’re thinking that these FDA-cleared apps seem pretty benign compared to the emotional and social effects of, say, AI companions, I agree.1

But how can we know without rigorous clinical testing?

The point isn’t to treat every online platform like a medical intervention. Rather, it’s to borrow the logic of the FDA model to require evidence about the emotional, social, and financial effects of high-risk online products like gambling, AI companions, social media, and pornography before permitting mass adoption.

Maybe the FDA isn’t the right agency. Maybe it’s the FTC, or perhaps we need a new agency designed from first principles and led by the country’s best technology researchers.

Any FDA-like approval process would generate dueling criticism that the process doesn’t do enough to ensure user safety — or that it’s too burdensome and costly for innovative startups. We saw similar, dueling narratives during COVID — that the FDA moved either too slow or too fast.

Andrew Tutt’s call for “An FDA for Algorithms” argues that lawsuits will always be years behind technological innovation. By the time the Character.ai lawsuits resolve, AI companion products will look and act fundamentally different. Tutt emphasizes the importance of matching regulation to risk. Low-risk apps might flourish under immunity, medium-risk under warnings and liability, and only the highest risk demand pre-approval. Establishing safety thresholds could help minimize bans while encouraging ethical innovation.

Consider two plausible futures of AI companions. A company like Yana.ai might help users build emotional self-awareness and social confidence. Another version, like BetHog’s flirtatious AI blackjack dealers, might manipulate young men’s loneliness, sexual desire, and risk-taking to deepen problem gambling.

Today’s calls for bans and exemptions treat Yana and BetHog as the same product.

A scientific approach, by contrast, generates causal evidence based on pre-specified outcomes. It creates an incentive for companies to prove that they enhance well-being, not compulsive use. And it equips researchers and regulators with tools to prevent harms in the first place.

Ravi Iyer, a former Facebook employee and now Managing Director of the Psychology of Technology Institute, offers a useful analogy: “We don’t make home builders responsible for every fire,” he writes, “but we do expect them to follow building codes.”

It’s not a binary choice between liability and evidence. Users should still be able to sue for harms after a product is authorized. Still, we should expect far fewer harms (and lawsuits) if high-risk platforms must first demonstrate their safety and benefits with credible evidence.

So what should we do?

Keep strong speech protections for low-risk contexts, where user choice is real and harms are limited.

Use bans sparingly, targeting minors and harm without benefit like nudification apps.

Allow legal liability as a backstop, especially when companies ignore known risks.

Build an FDA-style evidence pathway for high-risk platforms that affect the emotional, social, and financial well-being of users.

We don’t want to sanitize, moralize, or purify our digital experiences. In a liberal society, we ought to be able to take risks, seek stimulation, and learn from our mistakes.

But we’ve erred on the side of immunity for too long, prompting a pendulum swing to moral panic and calls for blanket bans. With nuance and evidence, online platforms can enhance rather than detract from our desire for fun, purpose, connection, and belonging.

This framework doesn’t eliminate tradeoffs, but it makes them visible.

In high school, I had to read The Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel about the unsanitary conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking plants. It sparked public outrage and pushed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drugs Act, which laid the path to the FDA.

Our online lives aren’t unsanitary, but they are increasingly unsavory. If we don’t want the politics of moral panic, we need the discipline of rigorous evidence.

If you’re interested in learning more and discussing an FDA-style precautionary approach to technology regulation, I hope you’ll join us for tomorrow’s Substack Live conversation with Rupert Gill, who proposes a precautionary approach to regulating AI companions and incentivizing ethical design. You can RSVP here.

The FDA requested public comment on the use of generative AI in therapeutic services, prompting recommendations and warnings from Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence and Data & Society, among others.

I think the FDA idea is interesting. In terms of your taxonomy though, it strikes me as potentially one level down of a 'regulation' umbrella category where an FDA-style could be one option, but more generally regulation should be based on some underlying evidence/science. In any case, I agree that we reach too quickly for the other categories, which all have sub-optimal longterm outcomes relative to regulation done well. One issue though with regulation is, at least in the U.S., it is hardly ever done well, usually taking way, way too long to get something passed, and then another generation before it is revisited. That's why I do think in this category some kind of agency makes more sense (like your proposal) since they have contiinous administrative oversight to adapt to new science. That said, the FDA style is just one approach. For example, the FTC often takes the approach of laying out rules but not requiring explicit approval, which could still be evidence based.

This is an excellent topography of the myriad approaches to government led tech reform! I’m curious if the threat of litigation might proactively incentivize safety-first design of AI chatbots absent direct legal action? (e.g. OpenAI parental controls, kids safety AI evals, Google’s child-proof model offerings)